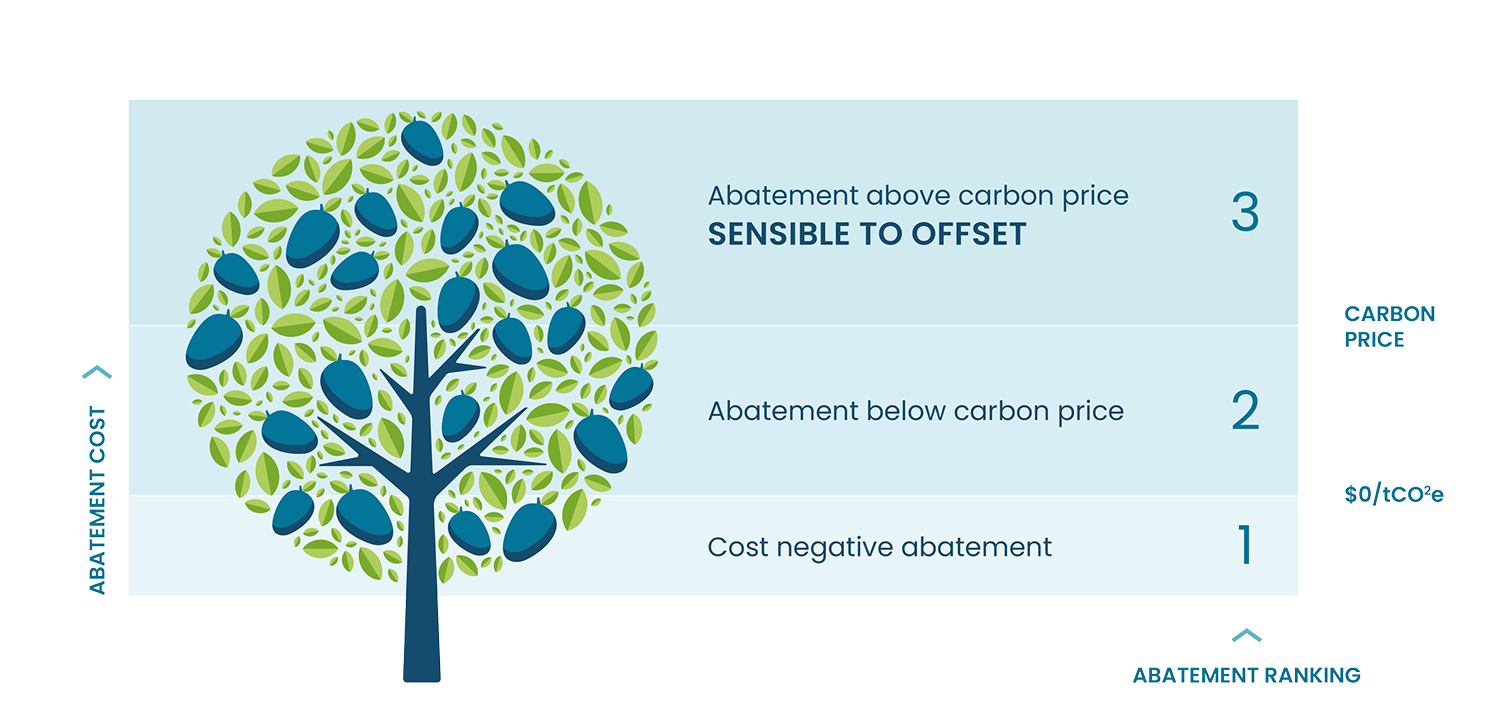

The Abatement Tree

The backbone economic logic underlying emissions trading is called the ‘marginal cost of abatement’. ‘Abatement’ here refers to reducing GHG pollution. The ‘marginal cost’ is the cost of the next piece of abatement that you do in a carbon reduction exercise. One way to conceptualise the marginal cost of abatement is to use fruit harvesting as an analogy.

An apple tree is covered with apples. But the cost to harvest the apples changes as you harvest them. After you walk around picking the low fruit, the low fruit are now all gone. You then need to jump to harvest the next layer up the tree, which requires more effort per apple. Then after those have all been harvested you need to use a ladder. Through time the harvesting effort per apple goes up a lot to the point where getting those last few apples takes a lot of effort (and cost) per apple.

The same happens with emissions reduction (abatement). One thing we discover when we measure our carbon footprint is that our abatement opportunities fall into different cost categories. Some are below zero (they save you money when you do them – such as reducing flights). Some are above zero but below the carbon price per tonne of CO2 abated (such as insulating a house). Others are both above zero and above the carbon price per tonne of CO2 abated. These are the low, medium, and high fruit on the ‘abatement tree’.

It is also worth noting that harvesting (abating) the highest fruit can be either a) prohibitively expensive – where harvesting this fruit would require the organisation to go bankrupt, or b) may be impossible at this stage on existing technology? For example, it is not possible to remove the embedded GHG emissions from the concrete manufacturing process for the concrete in your building. Or, for example, whilst reducing emissions by maximising efficiency within your fleet, it may not be achievable to convert your fleet to fully electric in the short term. Another example: it may not be possible or feasible at this stage to use a refrigerant that is not a greenhouse gas in your fruit processing plant.

Combatting climate change means getting the biggest beneficial bang for buck (the four ‘b’s) for every dollar invested in abatement. This means starting with harvesting all the low and medium fruit on the abatement tree across the entire economy. Ideally, climate policy and emissions trading are designed to do exactly that – harvest all the low and medium fruit and some of the high fruit. Unfortunately, the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme is not designed for this, but the voluntary carbon market is. Going Net Zero Carbon for example, is a voluntary action and falls under the voluntary carbon market.

When it comes to the cost of harvesting the highest fruit, however, a cost-benefit analysis would likely show that the four ‘b’s are not delivered by harvesting those highest fruit. The four ‘b’s are delivered when we stop harvesting high-cost abatement on our tree and instead pay to cause a higher volume of lower cost abatement on someone else’s tree. This is what carbon offsetting is.

The catch here is that someone else (i.e., the carbon offset project) needs to demonstrate that they could not deliver that abatement without the financial incentive in the form of the revenue from selling the carbon credits. This is called ‘additionality'. A good example is converting marginal farmland into permanent restorative forest cover. Here, the farmer cannot afford to turn off the revenue tap from that farmland (otherwise they will go bankrupt) and so they keep farming. But a forest carbon project allows the farmer to convert from one revenue stream (agricultural produce) to another revenue stream (carbon credits from permanent forest).

The goal is to combat climate change by doing as much abatement as we can and getting the biggest volume of abatement delivered by the limited funds available. We measure and reduce, and what we cannot reduce ourselves we either stop (still a good thing to do), or we decide to go the extra distance and take responsibility for the emissions that were too expensive or impossible to eliminate (an even better thing to do). Taking responsibility for these emissions involves carbon offsetting and, in the process, causing additional good to our planet – helping to recloak our whenua. When we choose a restorative forest carbon project to support (like any project supported by Ekos) then we will also contribute to biodiversity conservation, water quality, and climate resilience.